Conducting QuIPs in the context of Covid-19: Lessons from EduFinance

| 28 October 2022 | News

Last year we shared some reflections from our experiences of adapting and developing the QuIP approach in the context of the pandemic, highlighting how we had encountered both practical and methodological challenges. One of the issues we’ve continued to grapple with is how to facilitate conversations about changes over time without Covid-19 entirely dominating the causal narratives reported.

In the first few studies we conducted during the pandemic, our research teams tested using timelines to help focus respondents on different recall periods (i.e. pre-/post-intervention and before/after Covid restrictions). As we reflected last year, this seemed to work well, since respondents were able to share their perceptions and experiences which included, and went beyond, those affected by the pandemic.

Re-evaluating our approach

As we stated at the time, “as time goes on, and the impact of Covid-19 is perhaps more pronounced and long-lasting, this approach may need to be reconsidered.” That quote neatly summarises where we are today: pausing to evaluate our approach again. Covid-19 has featured as a root driver of (mostly negative) change in most of the QuIP studies Bath SDR has conducted or supported over the past two years. This is unsurprising and understandable, but we are keen to remain critically engaged with some of the potential issues we anticipated at the beginning of the pandemic.

One of the fears expressed by our team was that Covid-19 would become the sole focus of development research and programming, and/or Covid would become a convenient scapegoat to explain why interventions weren’t working as planned. Another concern was that recency and recall bias might influence how respondents remember events and construct their accounts of causal pathways, potentially overstating the influence of Covid-19 particularly for any negative outcomes experienced. Furthermore, as most QuIP recall periods are somewhere between one to three years, distinguishing between these time periods is increasingly difficult, even impossible.

A recent study with EduFinance highlights some of the challenges and benefits of using the QuIP approach in the pandemic.

The original aim was to explore school fee loan use in Uganda, but the research was delayed due to ongoing school closures, and eventually moved to Kenya where schools had at least reopened. A client survey previously developed and used by EduFinance was adapted to include open-ended QuIP-style questions covering key areas related to educational access and engagement, such as attendance and financing. Respondents were encouraged to discuss which factors acted as enablers or barriers to investing in their children’s education, and how this had changed (if at all) over the past three years.

Challenges using QuIP

One challenge encountered by the researchers was that respondents’ causal narratives were overwhelmingly centred around Covid-19. Despite prompting, they struggled to recall other drivers of change, as their livelihoods had been significantly affected by the pandemic. Of course, this may reflect reality, and it is important to value respondents’ perception – but it should be acknowledged that recency and recall bias may have contributed to the focus on Covid-19. One reflection from the research team was that the recall period of three years may have increased the focus on Covid and negative changes. Because respondents were asked to compare what life was like before and after the pandemic, they considered themselves to be in a worse position overall, and therefore mostly presented a more negative picture of their current state. It may have been better to use a shorter recall period and focus on post-Covid impacts, but in some cases this would compromise the ability of researchers to capture positive impacts of interventions pre-Covid.

Benefits of using a goal-free approach

The advantage of QuIP goal-free style of interviewing was that respondents could talk about the complexity and nuance of how things had changed over time, particularly with regards to Covid-19, which provided greater insight into how intended outcomes had been influenced by contextual and external drivers.

For example, whilst it was anticipated that parents would talk about the impact of school closures on their children’s education (parents reported closures negatively affected their children’s performance upon returning to school, as well as their wellbeing and behaviour during the lockdown), respondents were encouraged to construct their own causal narratives which highlighted other causal pathways, for example, how Covid-19 had also affected school attendance over a longer time period through impacts on parents’ income and the affordability of education.

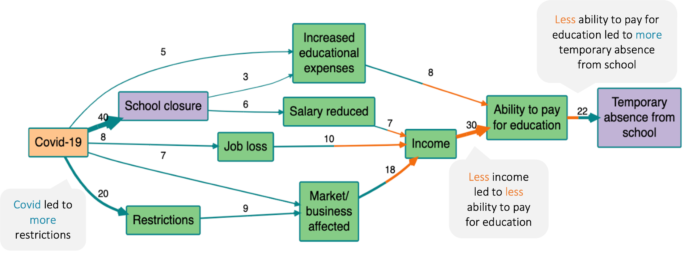

The causal map below illustrates the causal pathways between Covid-19 and school absence, showing both the direct influence on school closure and indirect influence through reduced income and increased expenses hampering the ability to pay for education. Note, orange links represent less of something, and blue links represent more of something.

Filters: zoom level 1, combine opposites, path tracing from factor ‘Covid-19’ to ‘School closure’ and ‘Temporary absence from school’, 2+ citation count

These findings emphasised to EduFinance how Covid-19 is likely to affect clients’ ability to repay loans and pay school fees for some time as they financially recover. This case study suggests that there is still a balancing act to master between enabling respondents to speak freely about their perceptions and experiences, whilst ensuring that their narratives aren’t overly preoccupied with the pandemic to the extent that they overshadow the evaluation of the programme.

However, programmes do not exist in a vacuum, and context is an important aspect of understanding causal pathways. It is therefore important to recognise that even where QuIP studies are designed to focus on evaluating programme impact during that reference period, they will be evaluating that impact in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic for some time, to varying degrees.

A few suggestions for future QuIP studies:

- QuIP commissioners should be realistic about the likelihood of Covid-19 featuring heavily in some causal pathways

- QuIP researchers need to prompt for how Covid-19 has affected respondents’ lives and livelihoods, to capture the nuance of these stories

- QuIP researchers need to encourage respondents to consider other factors which might have influenced any change experienced

Comments are closed here.