Guest blog: Using QuIP to evaluate Impact Networks

| 24 February 2025 | News,QuIP Articles

Impact evaluation methodologies are an evolving field, particularly when applied to network organizations. Dr Filip Zieliński attended a QuIP training course in 2024 and went on to conduct a pro bono impact evaluation of a German network of jazz venues to test the effectiveness of QuIP and the Causal Map App in the context of impact networks. This guest blog by Dr Zieliński shares some insights into the strengths and challenges of this methodology and practical implications for impact measurement and management (IMM).

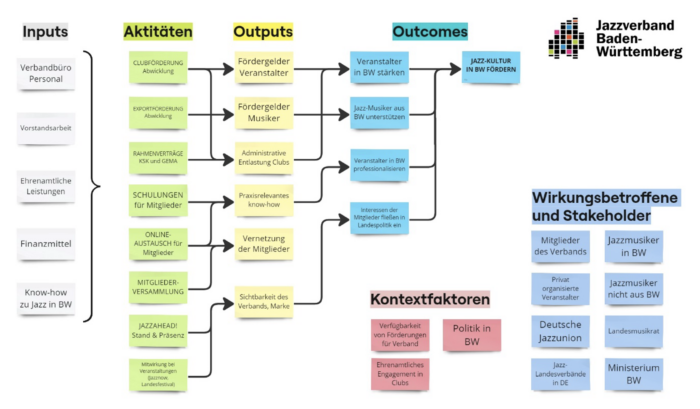

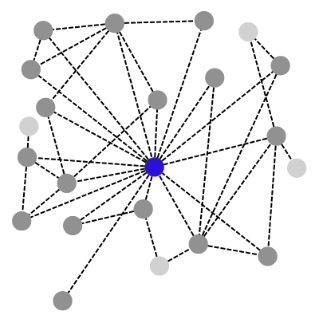

Impact networks are fascinating organizational “creatures”. They tend to be notoriously difficult to monitor and evaluate due to their de-central or multi-central character: In contrast to hierarchical, top-down organizations, impact networks bring together multiple, independent actors who connect, learn and collaborate with each other based on trust, reciprocity and a shared purpose. If the network maintains a network office, then its role is not to direct the network, but to facilitate connections between members (and non-members), including links between members without any involvement of the network office (see figure 1). For example, a network might intend to facilitate learning by building a Community of Practice for a sub-group of its members who will then exchange information and know-how directly, thus potentially increasing efficiency and enabling innovation. But how to monitor such learning, since it happens out of sight of the network office?

When it comes to the general internal or external evaluation of networks, the Converge network offers extensive (and free) resources that can be used i.e. to assess the health of the network or its connectivity (Social Network Analysis, Social System Map). Not surprisingly, much of the data for evaluation needs to be obtained from the members via surveys. In addition to these basic network evaluation techniques, impact networks are – naturally – also interested to assess in how far they actually contribute to the intended societal and/or environmental outcomes and impacts in the short, mid and long term and whether this comes with unintended or negative effects.

When it comes to the general internal or external evaluation of networks, the Converge network offers extensive (and free) resources that can be used i.e. to assess the health of the network or its connectivity (Social Network Analysis, Social System Map). Not surprisingly, much of the data for evaluation needs to be obtained from the members via surveys. In addition to these basic network evaluation techniques, impact networks are – naturally – also interested to assess in how far they actually contribute to the intended societal and/or environmental outcomes and impacts in the short, mid and long term and whether this comes with unintended or negative effects.

There is certainly a demand for impact evaluation methods that are suitable for network organizations, feasible for small and mid-sized organizations and able to address the crucial issues of methodological rigor and causal attribution. In this context, I have recently experimented with QuIP to evaluate two impact networks in the cultural sector (another evaluation for a business network is in the making) and would like to share my learnings and insights, provisional as they might be.

Approach

A key methodological choice was to use blindfolding, meaning that interviewees were not explicitly informed about the organization commissioning the study and the underlying assumptions. Blindfolding yields more unbiased and detailed responses, making it a crucial component of robust QuIP evaluations since it offers a solution to the otherwise powerful response bias. At the same time, un-blindfolding at a later stage of the interview ensures fairness to participants. Out of methodological curiosity, we added a counterfactual self-assessment question: “What would be different if the network organization did not exist?”, at the end of the interview, after respondents had been informed about the fact that the study had been commissioned by the network. Not surprisingly, answers were almost exclusively positive, completely centered on the office’s work and much less meaningful for refining the network’s Theory of Change.

The process of conducting and transcribing the phone interviews (17 twenty-minute interviews) and coding responses is somewhat time-intensive. In this project, it was done with the help of two undergraduate social science researchers, which worked well. At the beginning, all three of us coded the same three interviews after which we compared results, which helped to increase overall coding quality (inter-coder-reliability). The analysis of the coded material and writing up of the report proved to be the most challenging part of the project and requires strong expertise. Despite this, the methodology remains a viable and relatively affordable option for medium-sized and even some small organizations seeking to make a big step forward in IMM. Ensuring adequate resources and expertise for qualitative analysis is critical for obtaining meaningful results and social science research can play an important role in this regard, although financing remains an issue: The study at hand was made possible due to research funding provided by Heidelberg University and free of charge for the network, which is an unusual context.

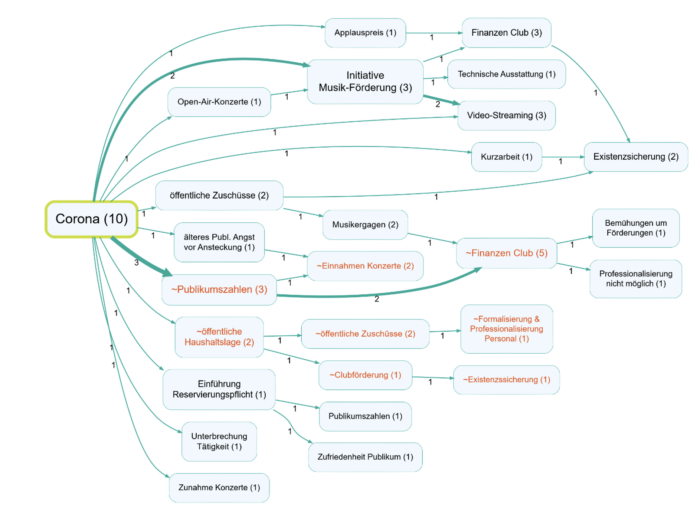

Results

A high share of respondents did explicitly state that the network generally contributed to better political representation on the regional level, which was in line with objectives. However, the interviews were not able to provide evidence for advocacy activities of the network, which is an important part of the Theory of Change of many impact networks. This is perhaps not surprising since members do not have the necessary insight into the actual advocacy activities of the network office and are therefore not likely to cite them as influences. To achieve this, we would need to collect data from additional stakeholders, e.g. interviews with key informants such as politicians and administrative staff of the regional ministry of culture.

For the other two parts of the ToC of the network, i.e. financial services and the Community of Practice, the QuIP analysis of the 17 member interviews proved to be very useful since members are aware of these areas in their day-to-day work. Regarding the financial services, the study offered very strong positive evidence that confirms the ToC’s causal pathways from inputs to outcomes. On the subject of the Community of Practice, results showed that some refinement and adaptation will be necessary in order to meet the intended outcomes of the ToC.

We also compared findings for members located in rural areas and those located in larger cities but found no significant differences. Interestingly, the interviews offered several new hypotheses as to which other categories might be relevant for the work of the network such as the geographical location within the region (center/periphery), the economic size of the venue and the difference between virtual and physical venues.

The network organization was highly satisfied with the evaluation outcomes, recognizing their value in strategic decision-making. As a result, there are plans to integrate IMM into their ongoing processes. The Theory of Practice workshop held at the project’s inception, together with the office team and board, despite lasting only half a day offered an opportunity to discuss and clarify the strategy of the network considering current contextual changes and stakeholder expectations, while keeping in mind the need for actionable evidence. Arguably, the ToC-workshop in itself is a very useful tool for IMM, regardless of how measurement is designed afterwards.

Using Causal Map

Causal Map offered strong analytical capabilities, particularly in its range of filtering and visualization options once interviews were coded. The ability to generate detailed causal maps is a unique feature not currently available in other QCA software. The workflow and stability of the web-based app could be further improved. [Note from editor: Causal Map has since gone through a significant update, including working on improved stability]. This being said, QuIP is a free-to-try and highly aligned tool that enables valuable analytic insights and ensures that researchers can always trace back aggregated results to individual quotes, when needed.

Conclusions

The initial findings of this ongoing research work underscore the potential of QuIP and Causal Map as effective tools for evaluating the impact of network organizations. However, methodological rigor, particularly regarding blindfolding, remains essential. QuIP offers the much-needed standards and norms to make the most of qualitative evaluation. While AI can play a role in expanding data collection, human expertise remains indispensable for in-depth analysis.

In 2025, we plan to test our QuIP-based approach with another network to gain further insights into how differences in network size (small/large networks) and sector (culture vs business networks) affect the application of QuIP.

If you are interested in this project, please do not hesitate to contact:

Dr. Filip Zieliński, M.A.

filip.zielinski@csi.uni-heidelberg.de

Resources

Website of the research project on impact measurement and management (IMM) for impact networks: www.soz.uni-heidelberg.de/impact-measurement-and-management-for-impact-networks-imm4in/

QuIP evaluation report of a network of jazz venues in Baden-Württemberg (in German): www.doi.org/10.11588/heidok.0003606910.11588/heidok.00036069

Comments are closed here.