Losing our way, learning how others explain change, and planning a new book…

| 15 March 2021 | Latest QuIP News

Much has changed since we published the book Attributing development impact, reflecting on lessons learnt conducting QuIP studies up until the end of 2017. There’s been Covid-19, the relentless digitalisation of our lives and climate change drama. Black Lives Matter has injected new energy into ‘decolonising’ international development practice or whatever remains of it. Meanwhile, Bath SDR has conducted and collaborated with many more QuIP studies – from Bolivia to Indonesia, Tajikistan to Mozambique. The way we code, analyse and visualise narrative data has been radically transformed, thanks particularly to Steve Powell, inventor of the Causal Map software. And we’ve begun to experiment with different ways of collecting data and jointly interpreting findings. This adds up to a lot of new material to reflect upon and to share. Enough to justify planning another book? Yes, we think so!

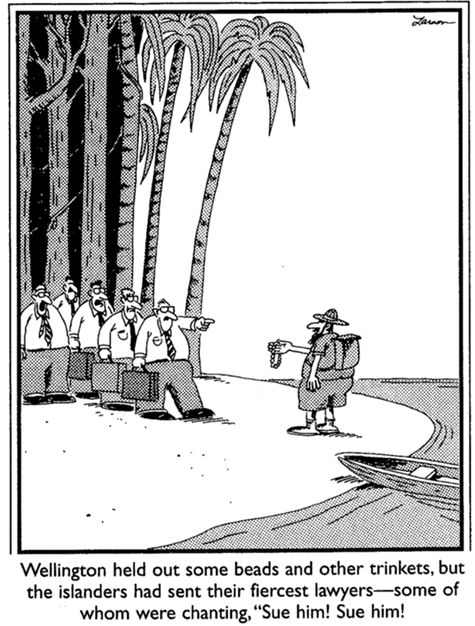

The core motivation for the first book was to point the way towards a credible, transparent, timely and cost-effective approach to evaluating the impact of a specified intervention (X) based on how intended beneficiaries themselves explained changes in different domains of their lives and livelihoods (Y). With hindsight, this was quite a narrow way of framing our work. Over time, we have found ourselves giving more emphasis to how QuIP studies reveal the different ways in which people explain social change, and the assumptions we they make about what other people think. The Gary Larson cartoon below captures the potential gulf between how social encounters are framed and perceived by different ‘stakeholders’ – differences that sit alongside and reinforce gaps in their material entitlements and interests.

Wayfinding – the art and science of how we find and lose our way – by Michael Bond – got me thinking further along these lines. He contrasts an “egocentric approach” to pathfinding – following your nose from one point to the next – with a “spatial approach” that involves taking a bird’s-eye view and capturing it in a cognitive map. Shifting from space to the time dimension, our brains enable us to generalize by integrating causal pathways through which we explain specific events (e.g. how we got from A to B) into a more general causal map (how A and B sit within a wider reading of history). More miraculous still is how language enables us to dream up a whole galaxy of other (imagined) histories: a creative cognitive leap to which Yuval Noah Harari attributes nothing less than our evolutionary ‘success’ as Homo Sapiens. In the more humble field of constructing credible claims about ‘what works, for whom and why’ in the field of international development we continue to grapple with how language, culture and perception mould the stories of change we tell and do not tell, the mental models we have of change, and the moral narratives that motivate us.

Moving up a gear, we are interested not only in individual narratives and cognitive maps, but shared mental models of change that fall somewhere between our explanation for one event and a general theory of ‘life, the universe and everything’. These middle-range theories or generalisations are what enable us to make imaginative leaps from our knowledge of one specific chain of events to what is likely to happen in similar but subtly different contexts. Communities of development practice coalesce around shared mental models of development that can usefully be analyzed in three dimensions: normative visions of how the world could be, historical understanding of how it actually is, and a practical vision of how the gap between the two can be reduced. Shared mental models that are credible in each dimension (normative, historical, practical) tend to gain popularity and influence. They may be useful and can sustain whole careers – in financial inclusion, impact investment, social protection, human rights, impact evaluation… But they are also potentially dangerous – the “thin simplifications” which James Scott memorably unpicked in his classic reflection on Why states fail. Whatever your favorite mental model of development may be at the moment, there is always a case for stopping, listening and spending some time reflecting on how you came by it, what it omits, and how it stacks up against the perspectives of others.

Which takes us back to QuIP, and the idea of another book. A modest goal for this would be to draw upon some of the additional studies we have done, supplemented by further reflections of those who commissioned, executed and contributed to them. Some potential chapters are already in the making: on the governance of artisanal mining in Sierra Leone, financial inclusion in Ghana, mixed method impact evaluation in Malawi, promoting agricultural supply chains in Nepal. Reflecting on what we learn from doing QuIP studies, and how we can do better fits with our motivation for setting up Bath SDR in the first place. But it would be so much better if we could locate some of this additional experience on a wider canvas of shared reflection about how we and others think about social change: how we are enthused by new visions of development, how we allow our heads to be conditioned by new and powerful ideas and techniques, how disjunctures and disconnects undermine collaboration, how we can emerge wiser through by self-reflection, and what we learn when we take the trouble to invest in finding out what other people were thinking too…

Cutting to the chase, this blog is an open invitation for you to offer thoughts, ideas and proposals that might contribute to and enrich a collaboratively produced book called something like Mental models of development: mapping how social change happens. We will particularly welcome contributions from those of you who have participated in carrying out and thinking about QuIP studies – itself a modest shared mental model. But we also hope to draw upon and be enriched by other experiences too. You can do this by contacting us via this link, and we’ll put you in touch with Hannah Mishan who has joined us to work on the book over the next few months.

Comments are closed here.