Interviewing adolescent girls in Kenya: Feed the Children

| 21 June 2021 | QuIP Articles

We are grateful for this guest post from Rosemary Nyaga, M&E Manager at Feed the Children. Rosemary completed an online QuIP Lead Evaluator training course in 2020 and went on to use the approach independently to evaluate a nutrition programme in Kenya – specifically working with younger respondents, a cohort which poses some specific challenges when conducting research of this kind.

We are grateful for this guest post from Rosemary Nyaga, M&E Manager at Feed the Children. Rosemary completed an online QuIP Lead Evaluator training course in 2020 and went on to use the approach independently to evaluate a nutrition programme in Kenya – specifically working with younger respondents, a cohort which poses some specific challenges when conducting research of this kind.

Why QuIP?

As M&E manager at Feed the Children, I was planning an evaluation of the Kajiado Nutrition Campaign, a programme targeting some of the issues contributing to intergenerational cycles of malnutrition in Kenya, such as undernourishment, obesity, and early marriage and childbearing. The campaign supports adolescent girls to build resilience and strengthen self-reliance through advocacy and nutrition education.

I first learnt about QuIP through a website called Better Evaluation that hosts a wide range of M&E content. Around the same time, Civil Society for Nutrition (CSN) Innovation & Research Fund, the SUN Civil Society Network Secretariat had launched a call for applications for the 2020 SUN CSN MEAL & Sustainability competitive grants. Feed the Children responded to the call and got funds to support the QuIP study among other interventions. One of reasons we chose the QuIP approach was the fact that the adolescent girls themselves would have a chance to share their own stories of change, hence making their perspectives heard. QuIP is also a more cost-effective methodology by virtue of its recommended number of interviews which worked better for this study due to our constrained budget.

The QuIP methodology was used to assess whether the campaign was achieving its intended objectives among the adolescent girls within the Oloilai and Engaboli Community Health Units and three selected schools within Kajiado. The study targeted girls aged between 10-19 years old, in and out of school, who had received food consumption and reproductive health messages in their schools through health club activities or from the peer-to-peer groups within their communities where mothers learn how to practice optimum nutrition behaviours.

The QuIP methodology was used to assess whether the campaign was achieving its intended objectives among the adolescent girls within the Oloilai and Engaboli Community Health Units and three selected schools within Kajiado. The study targeted girls aged between 10-19 years old, in and out of school, who had received food consumption and reproductive health messages in their schools through health club activities or from the peer-to-peer groups within their communities where mothers learn how to practice optimum nutrition behaviours.

This was my first experience using QuIP. I completed the Lead Evaluator accreditation course delivered by Bath SDR which was very helpful in building my capacity in the methodology. In addition, I found it useful to read quite extensively on available peer studies and have a mentor to technically backstop the process whenever faced with grey areas. An independent evaluator needs to be courageous enough to start the QuIP process and also be open to receive guidance from an experienced QuIP mentor. I feel that QuIP practitioners should be willing and available to support those new to the methodology to help popularize and develop it.

Challenges interviewing adolescent girls

The researchers conducted 24 QuIP-style interviews with adolescent girls. Interviewing adolescent girls was both interesting and intriguing. The dynamics of the interviews differed from data collection with adults in two key ways:

- it was important to use younger researchers who were near to the age group of the girls, and an all female research group

- more time was needed for the researchers to build trust with the girls and to conduct the interviews

- obtaining informed consent sometimes involved seeking multiple layers of consent from both the respondent and the parent/husband.

In the Maasai community, where the respondents were drawn, it is not unusual to find adolescent girls who are married, pregnant, or are already mothers. The community often reacts with suspicion to any outsiders engaging with adolescent girls privately because of the government child protection policies that may have been broken in those instances. Despite this context, the response rate was overwhelmingly good. The choice of same-sex young researchers (aged between 20-29) helped facilitate and ease the process of obtaining consent and conducting the interviews with the girls.

In the Maasai community, where the respondents were drawn, it is not unusual to find adolescent girls who are married, pregnant, or are already mothers. The community often reacts with suspicion to any outsiders engaging with adolescent girls privately because of the government child protection policies that may have been broken in those instances. Despite this context, the response rate was overwhelmingly good. The choice of same-sex young researchers (aged between 20-29) helped facilitate and ease the process of obtaining consent and conducting the interviews with the girls.

Using causal mapping

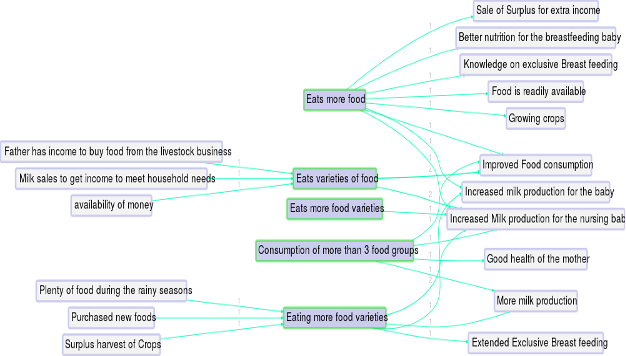

The data collected in this study was coded and analyzed using the Causal Map App which is a recent innovation made to code, analyse, and visualise fragments of information about what causes what.

Systematic coding of the causal stories told by the adolescent girls enabled deeper analysis of the causal pathways at play. Many of the narratives related to the availability and cost of food, livestock production, income, and seasonality. The above-mentioned drivers were reported to affect the food consumption habits of the adolescent girls in school and at home. The girls also shared how increased nutrition knowledge, sometimes challenging indigenous traditions on nutrition, was a key factor in influencing their food consumption habits both at home and at school.

Mapping these causal pathways based on the girls’ narratives highlighted the need for a holistic approach to adolescent programing that addresses the nutritional needs of the girls in a multi sectoral way.

Being able to disaggregate the data and look across the different purposefully selected groups revealed that there were different experiences of household relationships. For out-of-school girls, the husband was a focal point of reference; for girls in school and those out of school but not married, the parents (mother and/or father) were the focal point. Few adolescents were involved in decision making either by their husbands or by their parents. In most cases the males made most of the decisions, even on food consumption. While project interventions were targeted at adolescent girls, they had little or no role in decision making on food consumption in their homes, so a key recommendation following the research was for men to be involved in these interventions to to build a pool of future adolescent girl champions.

To find out more about this study you can watch a fantastic presentation given by Rosemary for a MEAL network webinar.

Comments are closed here.