Using QuIP to assess the impact of World Food Programme food systems support in six countries

| 9 May 2022 | QuIP Articles

The World Food Programme (WFP) Bureau in Johannesburg used QuIP as an opportunity to evaluate the real impact of WFP’s interventions whilst actively working to reduce potential confirmation bias in their research.

The World Food Programme (WFP) Bureau in Johannesburg used QuIP as an opportunity to evaluate the real impact of WFP’s interventions whilst actively working to reduce potential confirmation bias in their research.

This guest blog is written by Ludovico Alcorta – Director of Research, Southern Africa, Forcier Consulting

In 2021, following participation in QuIP training, the WFP team in Johannesburg commissioned Forcier Consulting to undertake a large study to explore the impact of the WFP’s activities on market development and related food systems support in Southern Africa. The evaluation planned to use the QuIP approach where possible, aiming to provide accountability and learning, with more weight on learning as this was a relatively new area of work for the WFP. It was an ambitious study covering work in six countries (Lesotho, Malawi, Madagascar, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe) from 2018 to 2021. WFP had collected some output data on market development activities in the past but this was the first time that they were examining their impact on the wider market.

The blog shares how Forcier went about planning the study, the logistical challenges of carrying out a QuIP of such size and scope and what we learned about the methodology from the experience.

Click here to read the full WFP report.

Data collection

No uniformed staff were used in the collection of QuIP data!

Understanding the real impact of interventions in evaluations can be a challenge; directly asking respondents about projects can bias results. To address this challenge, the QuIP approach specifies interviewing respondents with as little reference as possible to the specific activity being evaluated to give equal weight to all drivers of change in the domains of interest. This is done by working, where possible, with field researchers who are ‘blindfolded’ from knowing the identity of the organisation being evaluated, the details of project implementation and the theory of change behind its actions. This approach helps to keep interviews open-ended and build a detailed picture of what has really changed and why, however it is not without its challenges.

Over four months, WFP worked together with six country offices to design the country- and regional-level theory of change framework and finalise details of the study. The inception phase was prolonged due to the challenges posed by coordinating with six offices, all with their own schedules and priorities. Since Madagascar and Tanzania WFP country offices were at an earlier stage with interventions, their impact would have been challenging to measure in a traditional QuIP and therefore no Quip interviews were conducted in these 2 countries. Data was collected from May to July 2021, with Forcier conducting fieldwork in Mozambique and Lesotho and subcontracting local researchers in Malawi and Zimbabwe for data collection. A country-staggered approach allowed the training to be adapted and improved after each round. This also helped to keep the amount of fieldwork going on at any given time manageable.

The socio-political environment in many of the countries we worked in is sensitive, meaning people are rather sceptical when someone approaches them about participating in a study without informing them who the sponsoring organisation is. We were often able to get around this by explaining to participants the reasoning behind the blindfolding approach or replacing them with another respondent, but this was not always possible.

Snow in Lesotho!

The context in each country posed unique challenges! For example, in Lesotho fieldwork was halted for a few days because of a snowstorm, and during this time, the researchers attempted conducting remote interviews. However, the researchers found that respondents were not willing to participate in blindfolded interviews over the phone due to a wariness of phone scams, and the researchers had to wait until they could conduct interviews in-person again.

In Mozambique, quite a few retailers thought we had been sent by the government food inspection agency to audit their shops and so refused to participate.

We ran out of respondents willing to engage with a blindfolded approach and therefore took the decision to lift the blindfold to complete the study in Mozambique.

Data analysis

Data coding was a lengthy process, as there was a significant amount of data to go through (6,000 statements!), and we were new to the Casual Map app which we used to code and analyse the data using the QuIP approach.

A team of two coders coordinated with one another to keep their coding approach synchronised, using shared factor labels to code any links people made between cause and effect. The data for each country took about two weeks to code and comparing these countries took an additional two weeks. We worked with the developer of the Causal Map App (Steve Powell) to create overarching regional causal maps with common factor labels to make the data manageable.

The resulting evaluation allowed us to better understand the impacts of different types of interventions across the region.

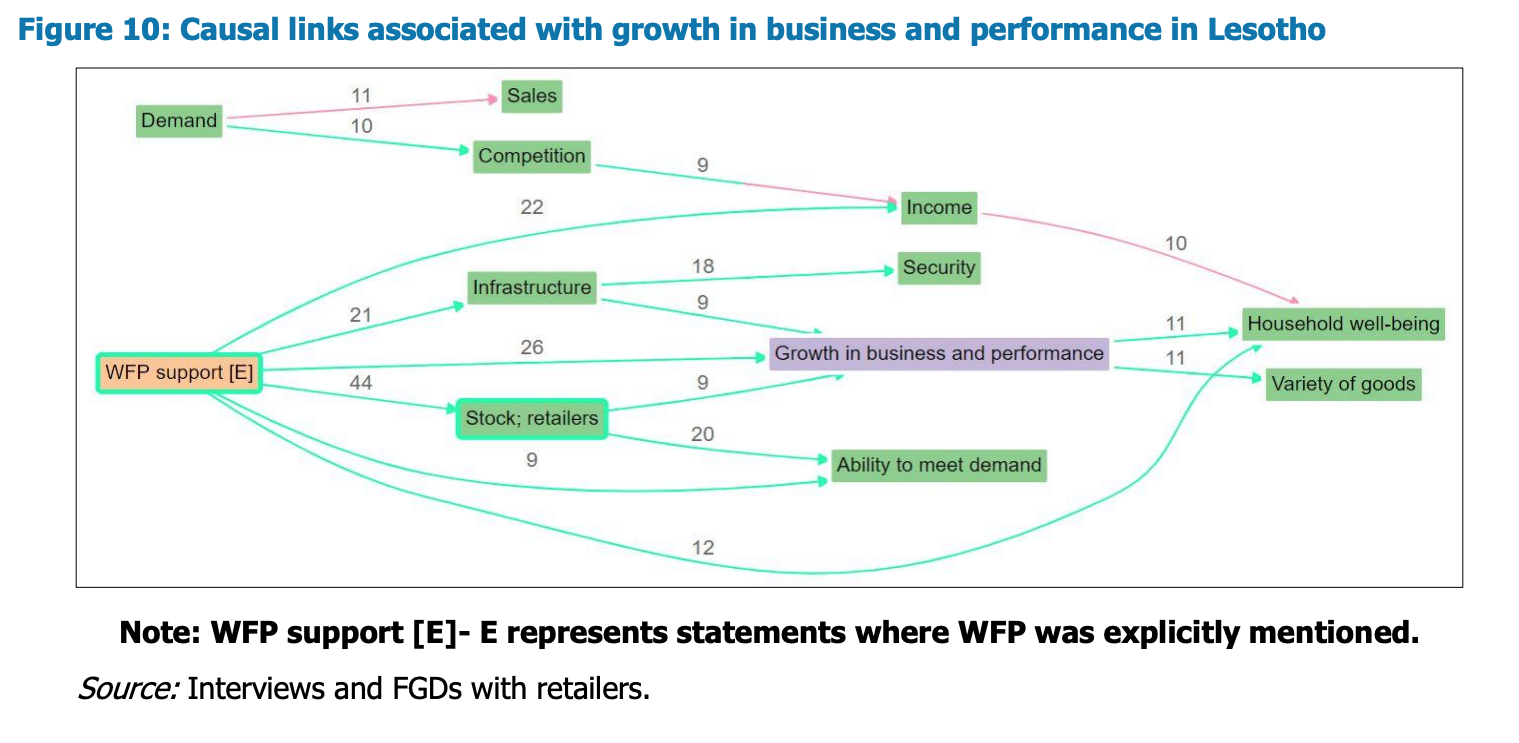

For example, in Lesotho, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe, the interventions were cash transfers with restrictions on use and linked to specific market actors, and these activities were reported to have noticeable and sustainable effects on the market.

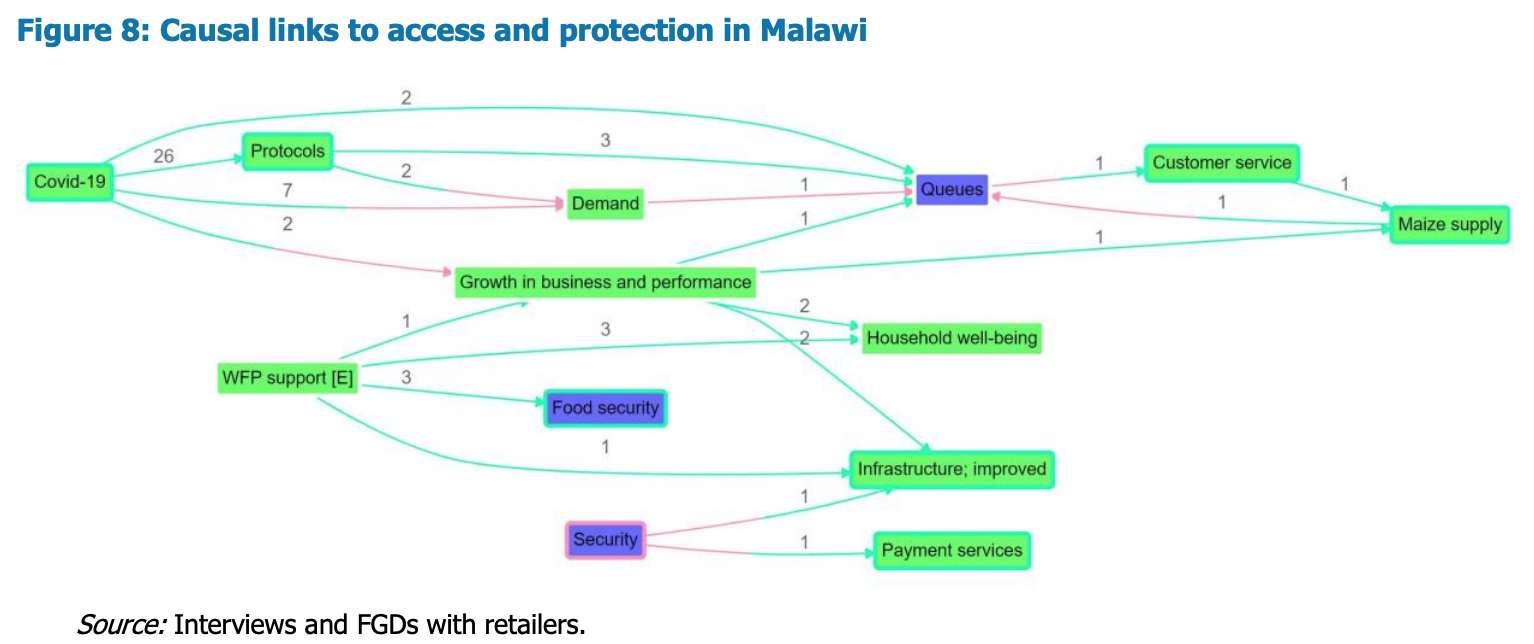

On the other hand, in Malawi the cash transfers had no restrictions on use, and it was very difficult to identify whether WFP was the source of the financing. The QuIP reflected this with very little attribution made to WFP in Malawi compared to other countries.

The limitations in data collection were in some ways a strength because the unblindfolded interviews provided us with enough variation in the data to compare and observe that there was substantially less attribution to WFP in the blindfolded interviews.

We decided from the outset not to use the blindfolding approach in Zimbabwe because we felt we would have very little respondent engagement. When coding the data we found that the attribution to WFP was considerably higher in Zimbabwe than in areas with more blindfolded interviews. However, we had no blindfolded interviews in Zimbabwe to verify whether the increase in attribution to WFP reflected the national context or was a result of confirmation bias in the data collection.

Overall, we found that the interventions had a positive impact on market functionality but were not the only factors at play. By focusing on all drivers of change, the study was able to place WFP in the context of the wider market forces, such as Covid-19 and market demand. This was important as without the outcome-based approach that QuIP offers there would have been the risk of exaggerating WFP’s role in the observable changes.

We feel that QuIP’s blindfolded approach reduced respondent confirmation bias and the coding undertaken in Causal Map allowed for a visually engaging cross-country comparison of qualitative data. Furthermore, it was done in a cost-effective manner that would not have been possible using a representative quantitative approach. For other issues we faced in this study and how we dealt with them, please see page 15 in the full report.

Comments are closed here.